This presentation starts a process of renewal and renovation within the MAK Permanent Collection, with the opening of three newly designed and installed galleries (unchanged since 1993). These spaces are devoted to the development of Viennese arts and crafts between 1890 and 1938 and are intended to position the MAK and its collection as an international center of research for Viennese Modernism. The permanent exhibition display is conceived as a “work in progress.” In its first phase, designed by Viennese architect Michael Embacher, the conceptual framework developed by Christian Witt-Dörring, in collaboration with the MAK collection curators, is embodied by collection objects, which are for the most part relatively unknown to the public.

The opening of the new MAK Permanent Collection Vienna 1900 is on September 19, 2013.

In Search of a Modern Style

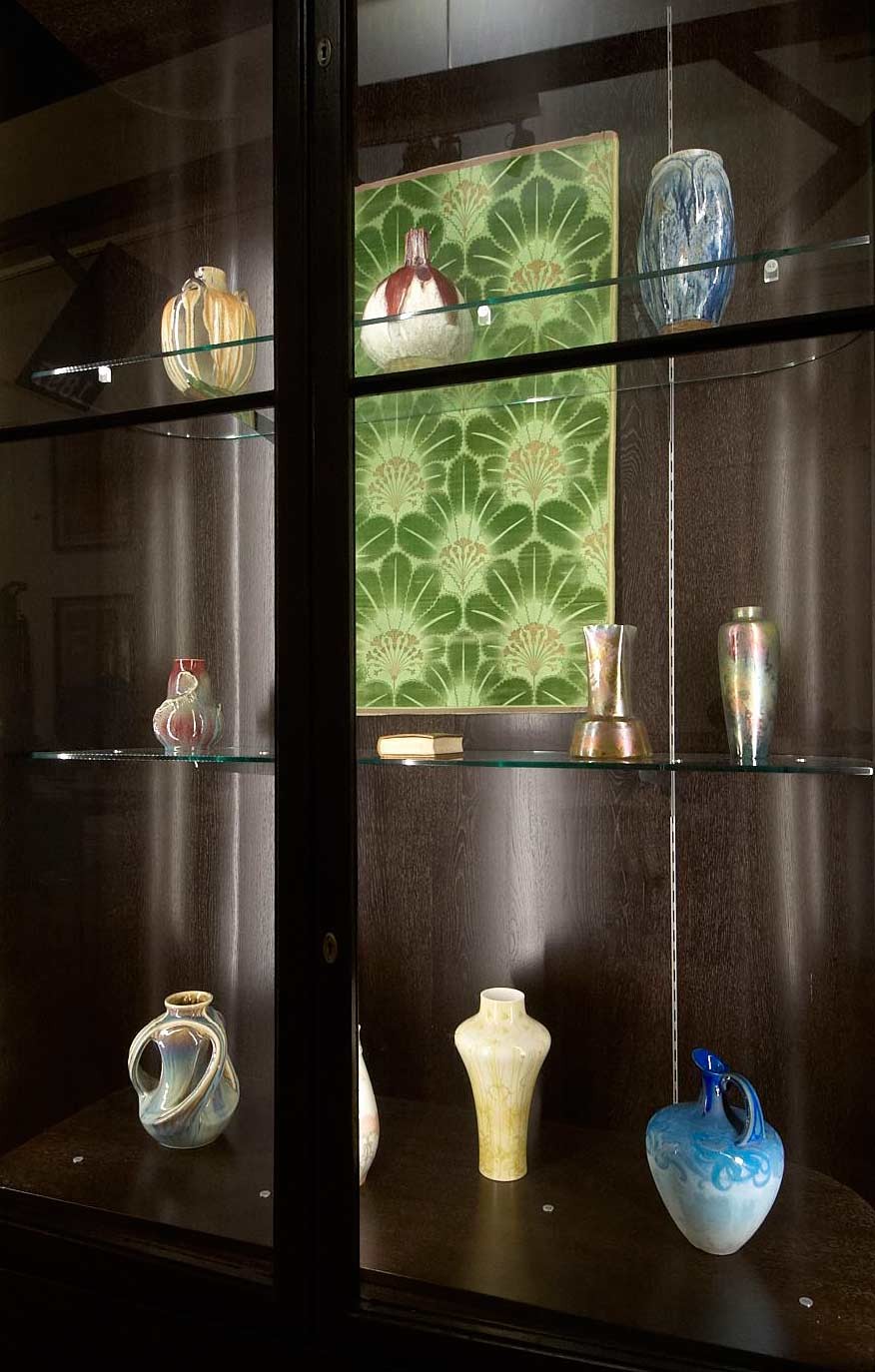

The search for a modern Austrian style in the years 1890 to 1900 led to an overcoming of Historicism. The objects exhibited in this gallery are largely contemporary acquisitions of products from abroad, in particular, Great Britain, Holland, France, and Germany, where reform moves had already been successfully implemented. Also included are examples of Japanese industrial arts, which were likewise seen as exemplary. These acquired pieces were meant to introduce the line of products that the museum considered commendable, especially to the industrial arts training institutes scattered throughout the monarchy. Results of this role-model function are represented in individual works by students at these technical schools.

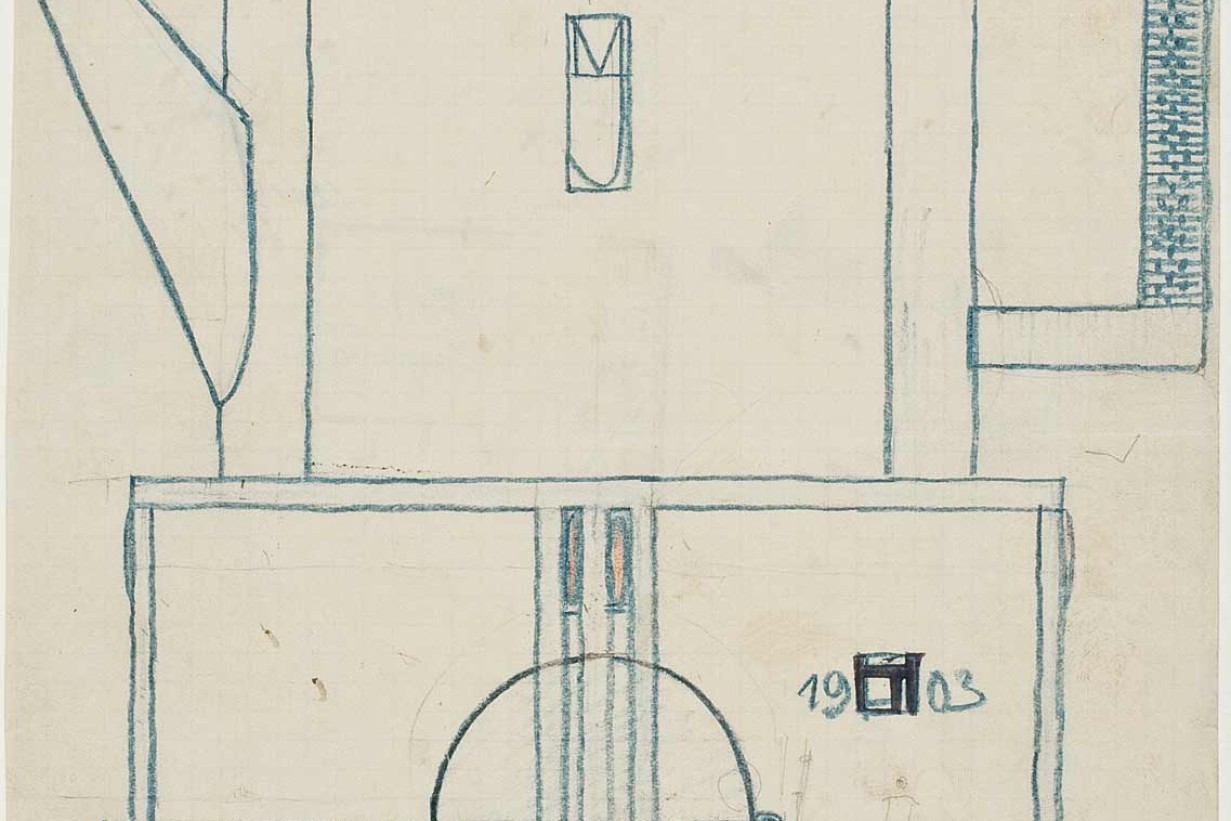

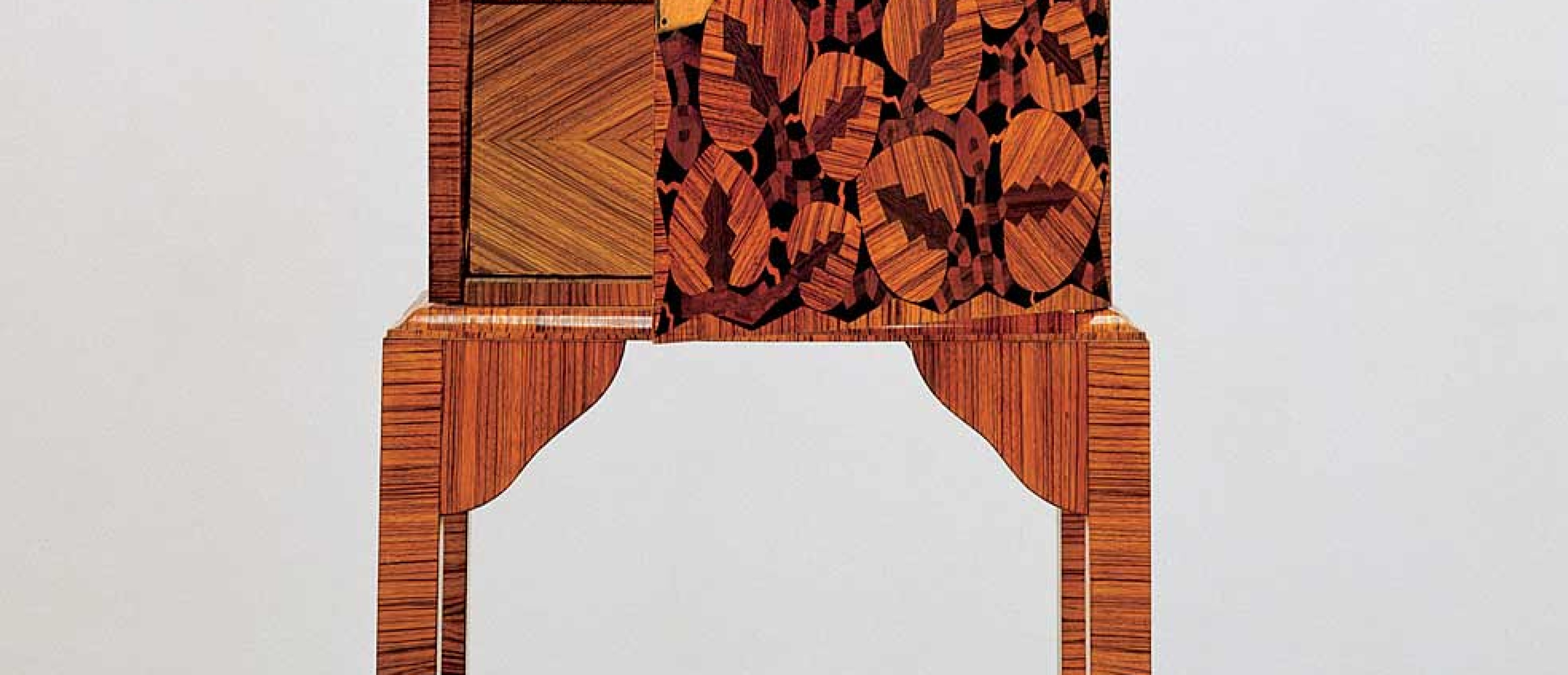

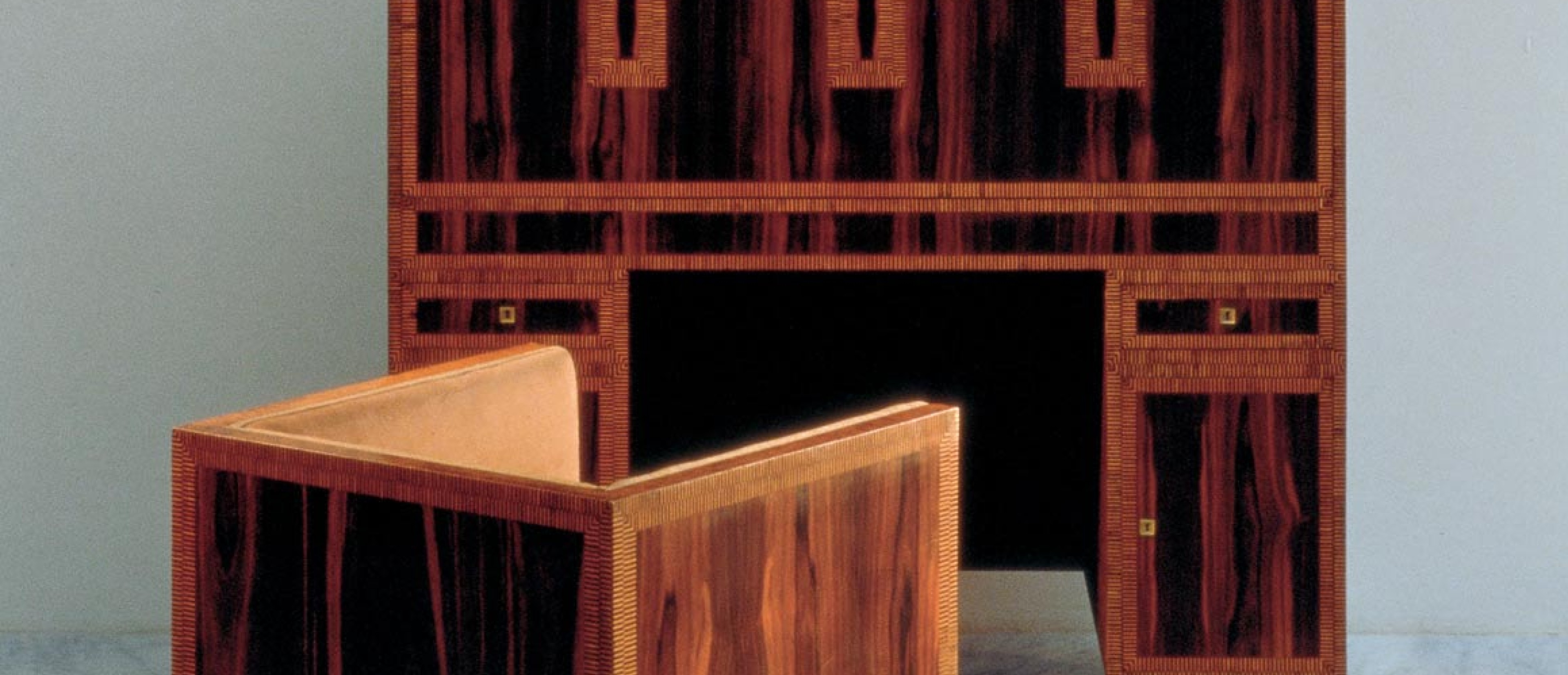

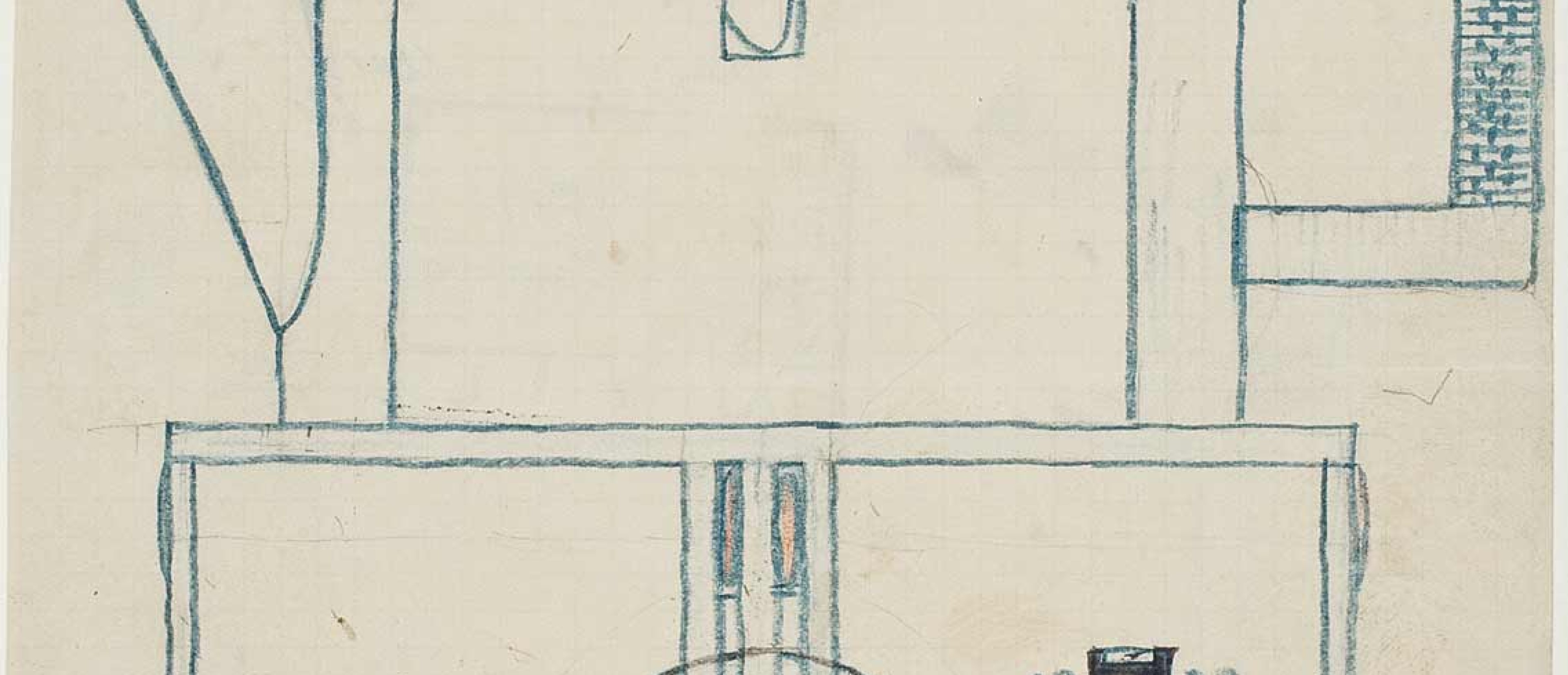

Already in 1899, Otto Wagner made his demand for a functionalist style, setting the path for the development of Viennese Modernism. This is made comprehensible here by the first piece of “modern” Viennese furniture, a cupboard he designed for his own home in 1899. Wagner also represents the immediately embarked upon, distinct Viennese road to Modernism. Although at first still largely defined by the curvilinear forms adopted from Belgium and France, which represent a conscious reference to the Ludwig XV era, beginning in 1900, Vienna recalled its own national roots and arrived at a geometrically abstract form via the local Biedermeier tradition, which at the time was erroneously identified as the first “bourgeois” style. Moser’s buffet The Rich Catch of Fish from 1900 marks this change in direction with regard to form. And finally, Adolf Loos’ alternative road to Modernism, opposing the Secession’s idea of a Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art), has a say by means of a lounge chair from the smoking room of Gustav Turnowsky’s apartment. Christian Witt-Dörring

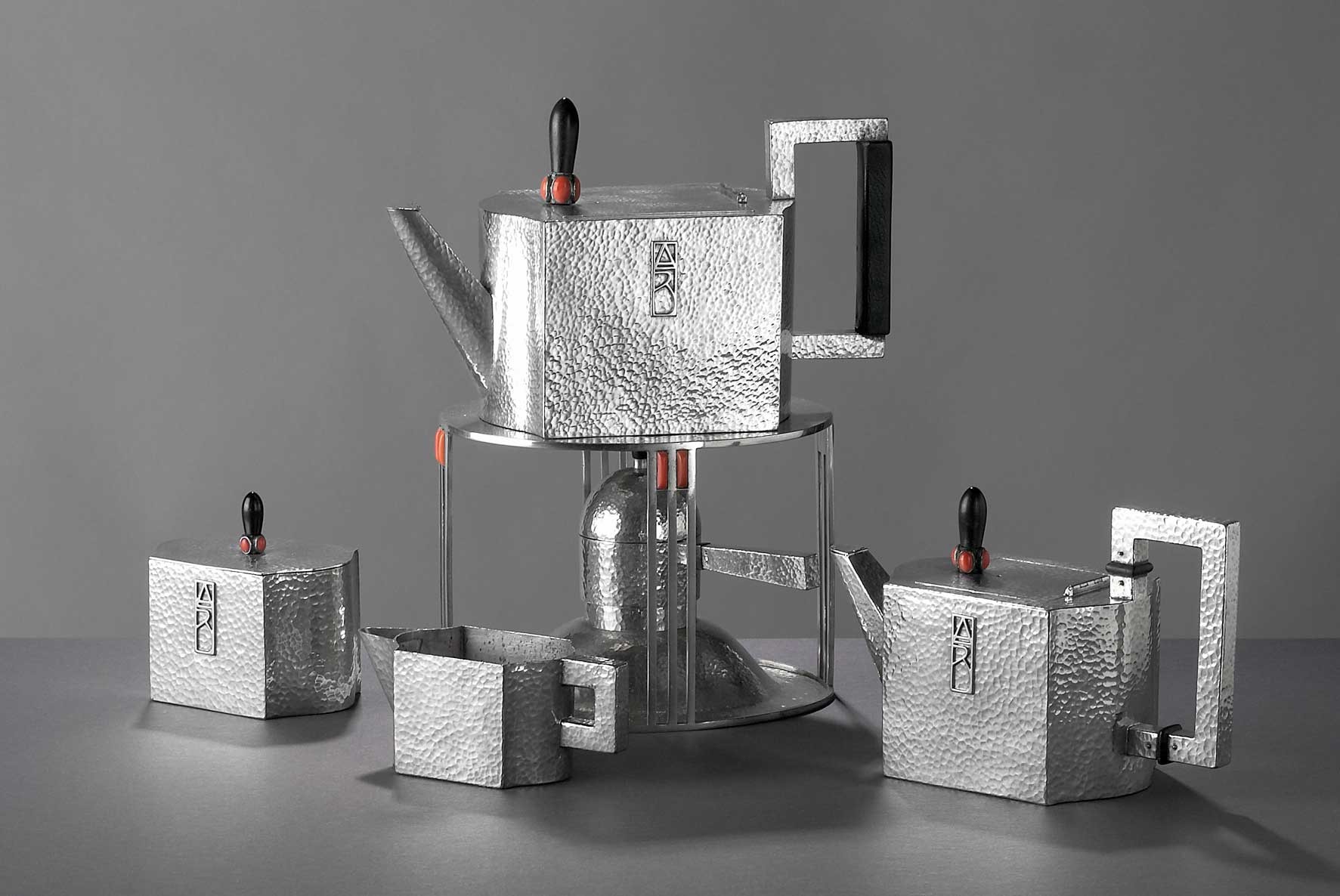

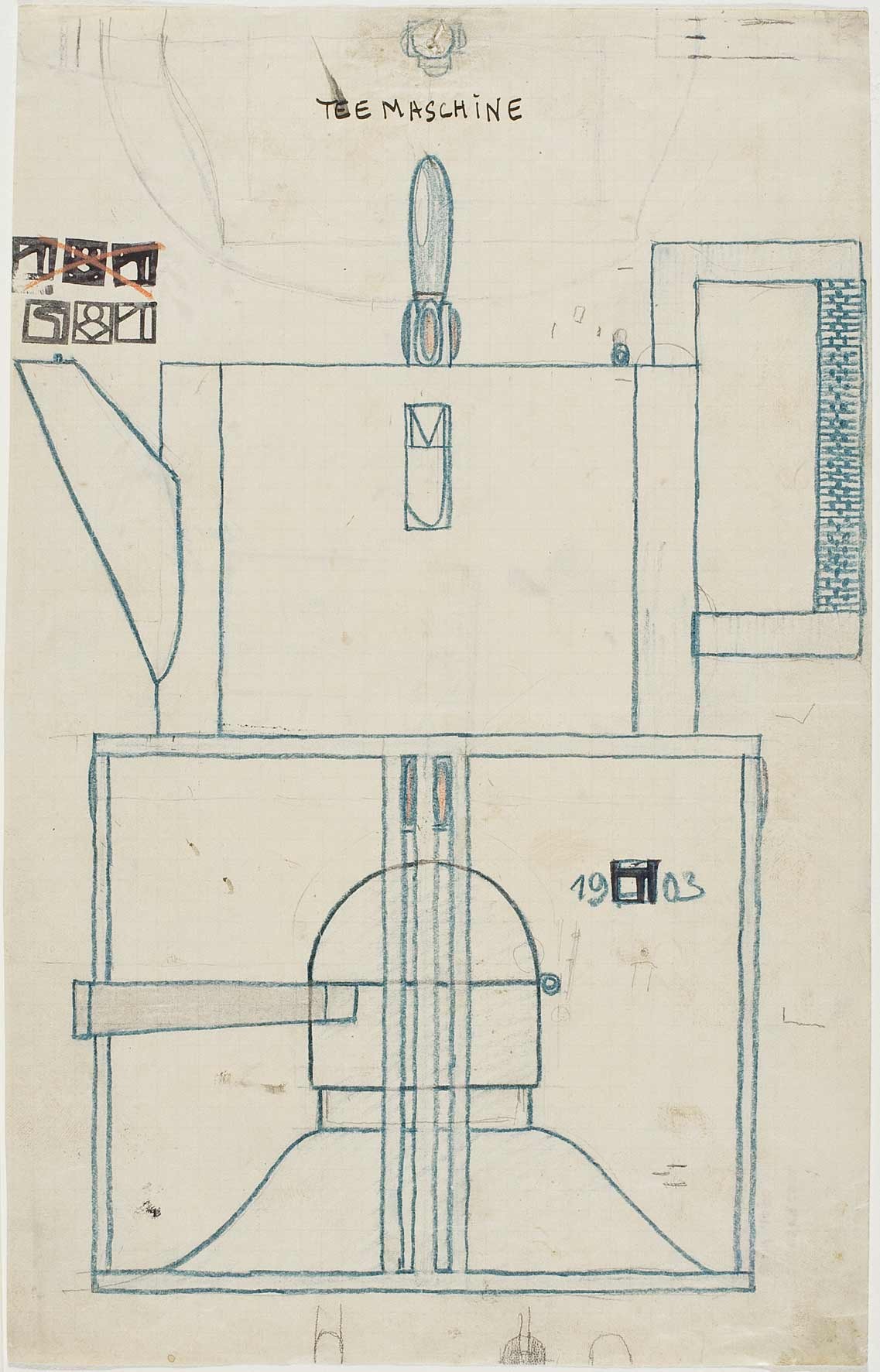

The Viennese Style

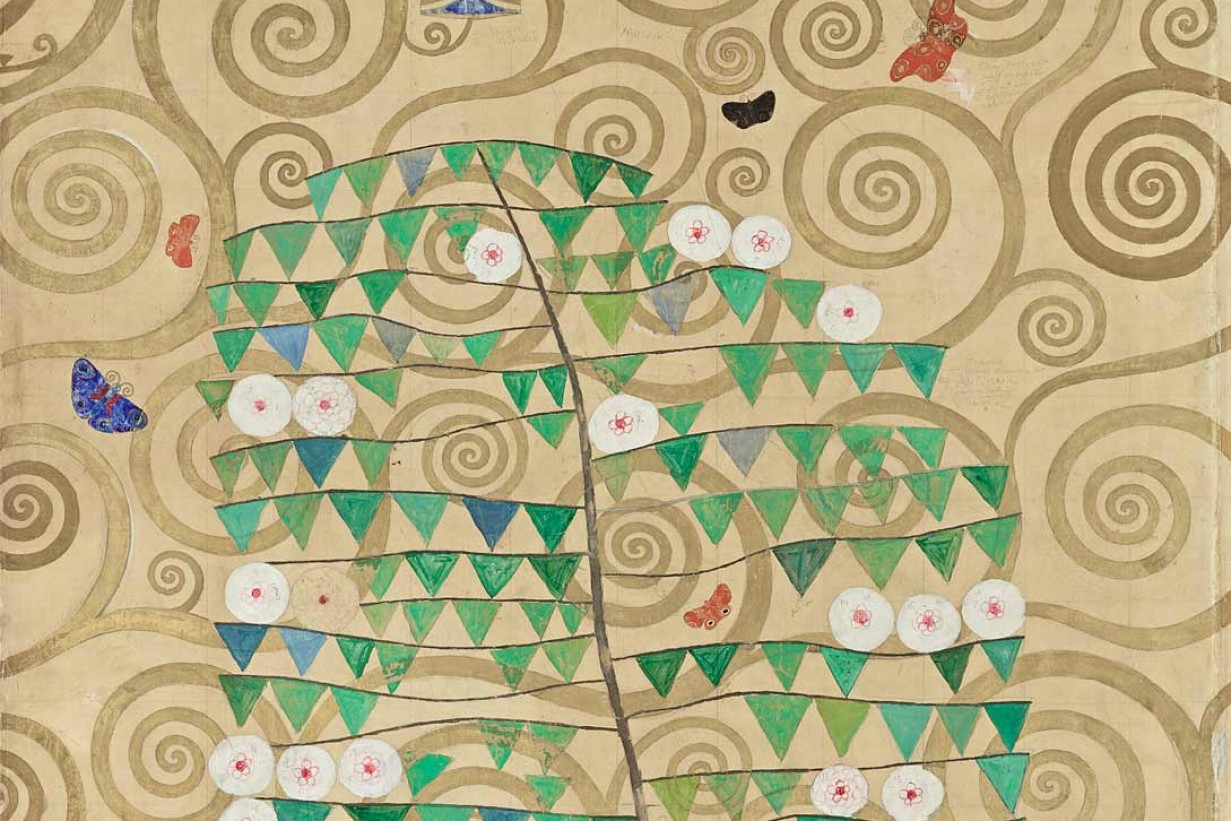

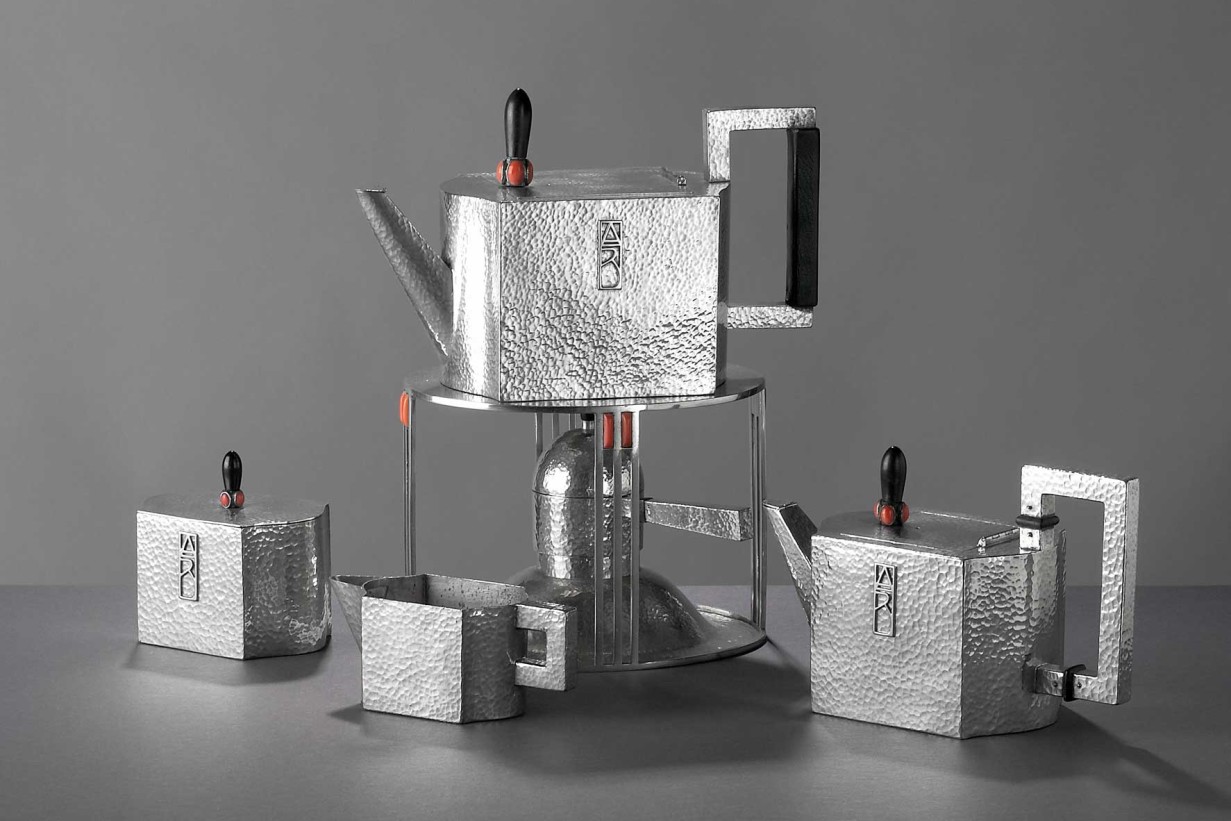

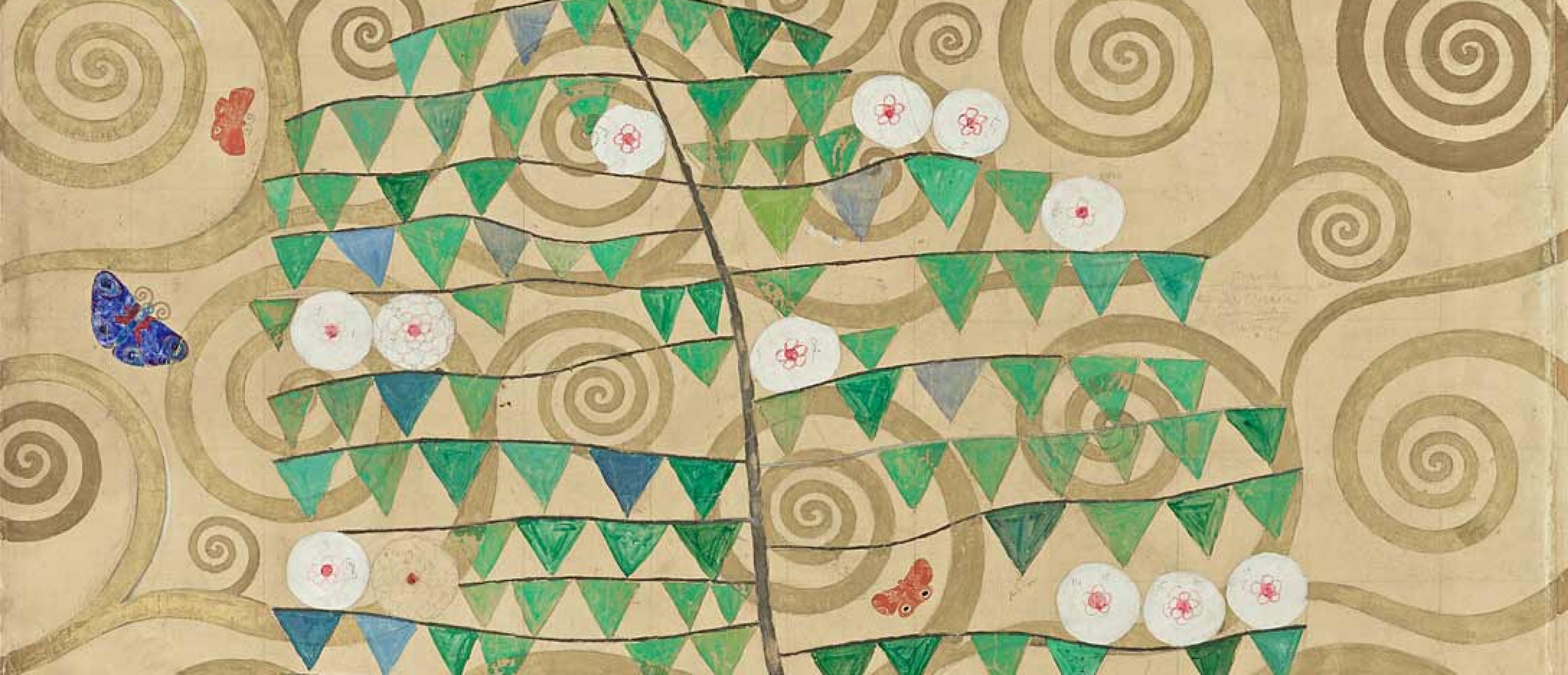

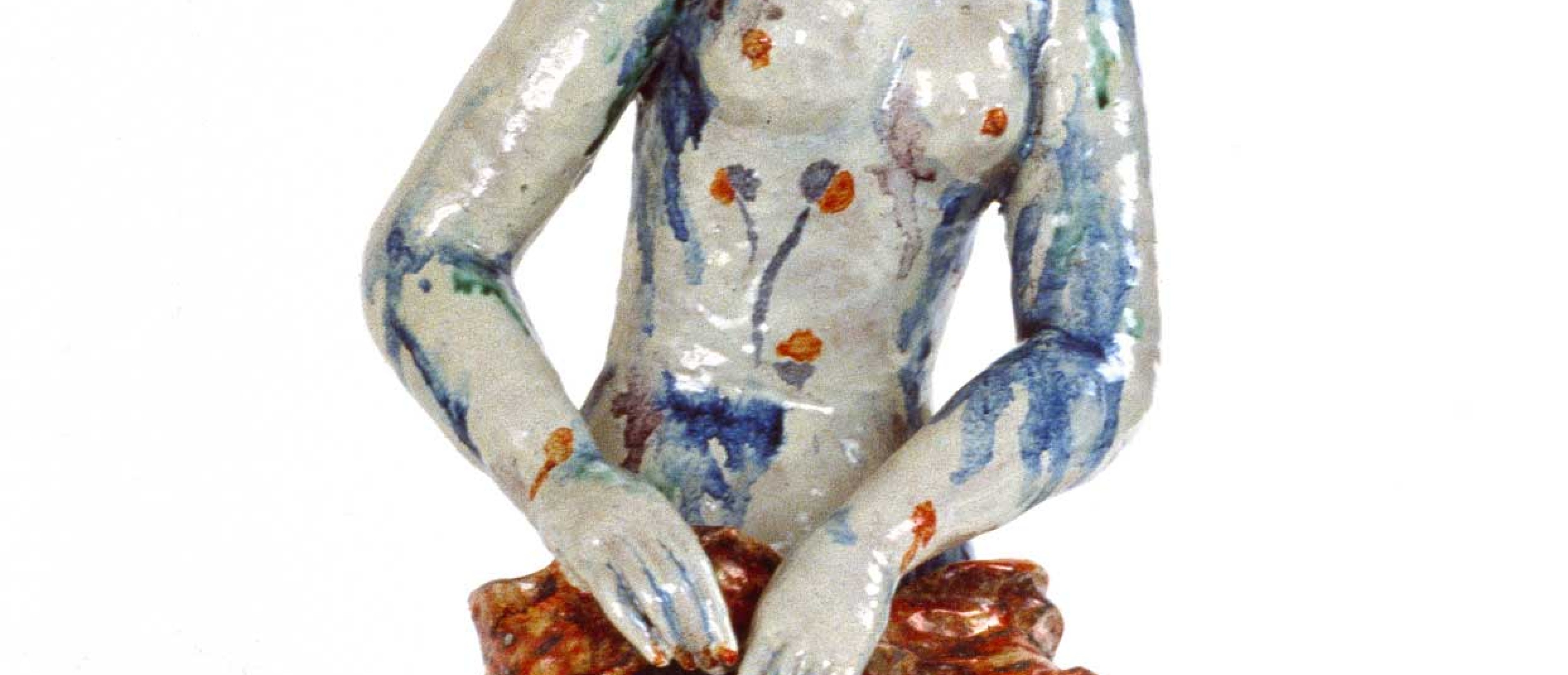

Loos’ cultural modernism was blatantly opposed by the formal-stylistic Modernism of the Secession, and along with it, the School of Arts and Crafts and the Wiener Werkstätte, to whom this gallery is devoted. For Loos, the question of Modernism was a matter of attitude and did not rely on the development of a modern style specified by artists. For him, the idea of unifying art and function within a use object was an act displaying a lack of culture. Only Otto Wagner was conceded the ability of an artistically implemented functionality as he did not place artistic expression above the crafts tradition. He hereby reacted to the English Arts and Crafts Movement’s conviction that the Secessionists had adopted whereby beauty, mediated through artistic design, is capable of improving people’s everyday lives.

From Viennese Style to International Style

The third and final gallery is distinguished from the previous two by not only the later date of origin of its exhibited pieces, but mainly, a much more heterogeneous diversity of tastes. This likewise addresses a characteristic feature that although self-evident today, was new for the Austrian interwar period. Heterogeneity of tastes is able to emerge when a democratic disposition acknowledges individual needs and finds acceptance, and when the market serves a mixed class of buyers. The enormous social transformations after World War I presented Modernism with a new challenge in this context. While, on the other hand, new forms of representation arose, on the one hand, specific solutions were offered to social classes of which the creative world had previously been practically unaware.

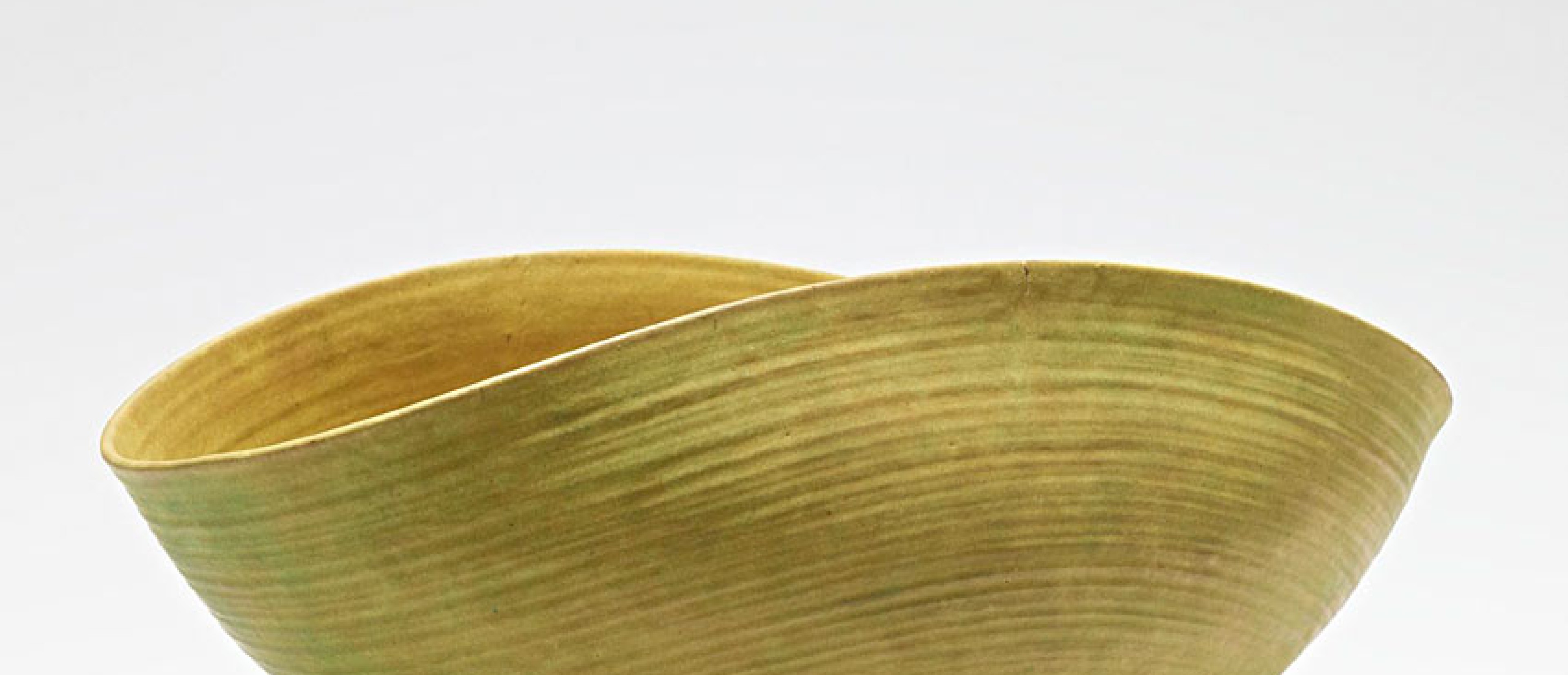

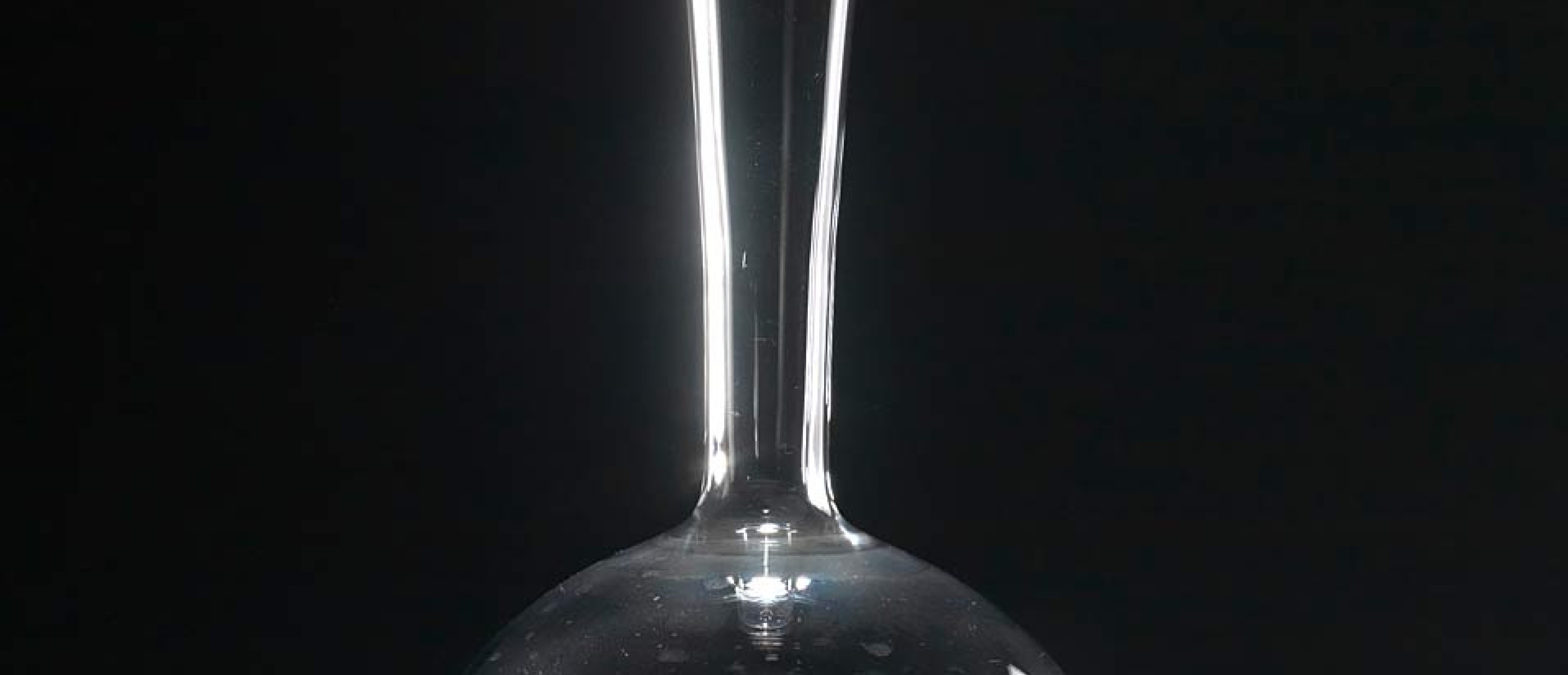

Since the founding of the Vienna Secession and the subsequent reaction by Loos, a new generation of designers had evolved that questioned the old representation forms and championed International Modernism’s world of forms. At the same time, in contrast to Germany, which already in the early days of the twentieth century had taken a positive stance toward industrial production’s possibilities in terms of formal aesthetics and faced up to its social market reality, in Austria, the Secessionists’ enthusiastically-adopted Arts and Crafts tradition of exclusive artisanal production remained vibrant. Representative of that are the elaborate handmade objects purchased on the occasion of the exhibition Das befreite Handwerk organized by the Museum for Art and Industry in 1934.

The Secessionists’ propagated unity of the arts, which lent use objects the status of artworks, had nonetheless become outdated. The awareness of quality achieved in connection with Loos’ cultural-critical ideas, however, yielded fruit revealing a specific Viennese solution along the road from Viennese style to International Style. It’s most clear-cut characterization can be found in Josef Frank’s proclamation: “Steel is not a material; Steel is a Weltanschauung.”

The National Socialist takeover of power in Austria in 1938 resulted in a leveling of individuality, as is characteristic of totalitarian regimes, and signified the end of a distinct Viennese use of forms. Christian Witt-Dörring

Vienna 1900 / Stage 1: 21.11.2012–23.06.2013

The curatorial approach

The contents of this permanent collection display reflect that in the arts and crafts of Vienna circa 1900, as in the rest of the Western world, modern people were searching for new objects that formally expressed their needs. This narrative of formal-aesthetic identity-building, and its assessment, is set against an extended time frame from 1890 to 1938 in order to facilitate the understanding of cause and consequence. Each of the presentation’s three spaces is assigned a theme. They tell the story of the search for a modern style from the emergence of a uniquely Viennese style through the confrontation of the Viennese style with International style, and end with the national socialist takeover of power in Austria. As is characteristic of totalitarian regimes, this resulted in the leveling of individuality, and signified a temporary end for a distinctive Viennese style.

Curator Christian Witt-Dörring

Design Embacher Wien

OTHERS

curated by Pae White

Wed, 21.11.2012–Sun, 23.06.2013

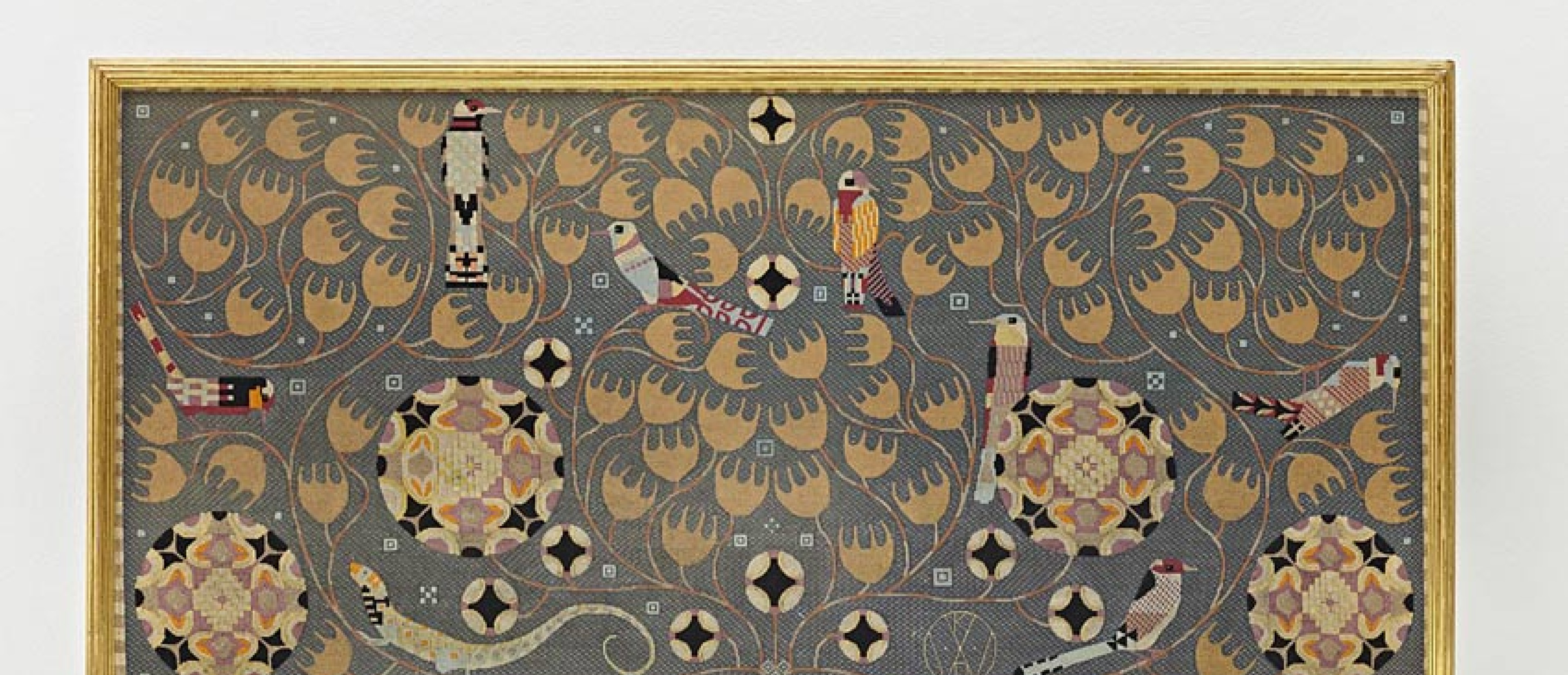

The new presentation is a project by artist Pae White titled OTHERS. White has selected works-on-paper and three-dimensional objects from the MAK Permanent Collection whose authors are principally unknown. A major focus of White’s exhibition is the MAK’s extensive holding of Japanese stencils (katagami), largely

unauthored works on paper that have inspired several generations of European artists and artisans in their designs for textiles, coverings, and book illuminations. Pae White affirms that OTHERS is an attempt to rescue some of these objects, from relative obscurity, and to let them bask in the light of day.

Guest Curator Pae White

Exhibition OTHERS

Pae White

ORLLEGRO

In her work, Los Angeles-based artist Pae White develops new relationships between fine and applied arts, architecture, and design. In the context of her first solo exhibition in Austria, White is planning a large tapestry articulated in metallic thread, as well as a series of sculptures and objects especially for the museum. The MAK Permanent Collection— as revealed in Vienna 1900—serves as an inspiration for White, who is using her solo show to rethink what the applied arts mean to contemporary audiences.

Curator Bärbel Vischer, Curator

MAK Contemporary Art Collection

MAK/ZINE

The exhibition is accompanied by MAK/ZINE #2 2012, edited by Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, texts by Philipp Blom, Paul Foss, Christopher Hailey, Frank Hartmann, Owen Hatherley, William M. Johnston, Christoph Thun-Hohenstein, Johannes Wieninger, Christian Witt-Dörring, et al., German/English, ca. 120 pages, MAK/ Volltext Vienna 2012. Available at the MAK Design Shop for € 9.90.

Part of the exhibits will be integrated in the EU-funded project Partage Plus– Digitising and Enabling Art Nouveau for Europeana:

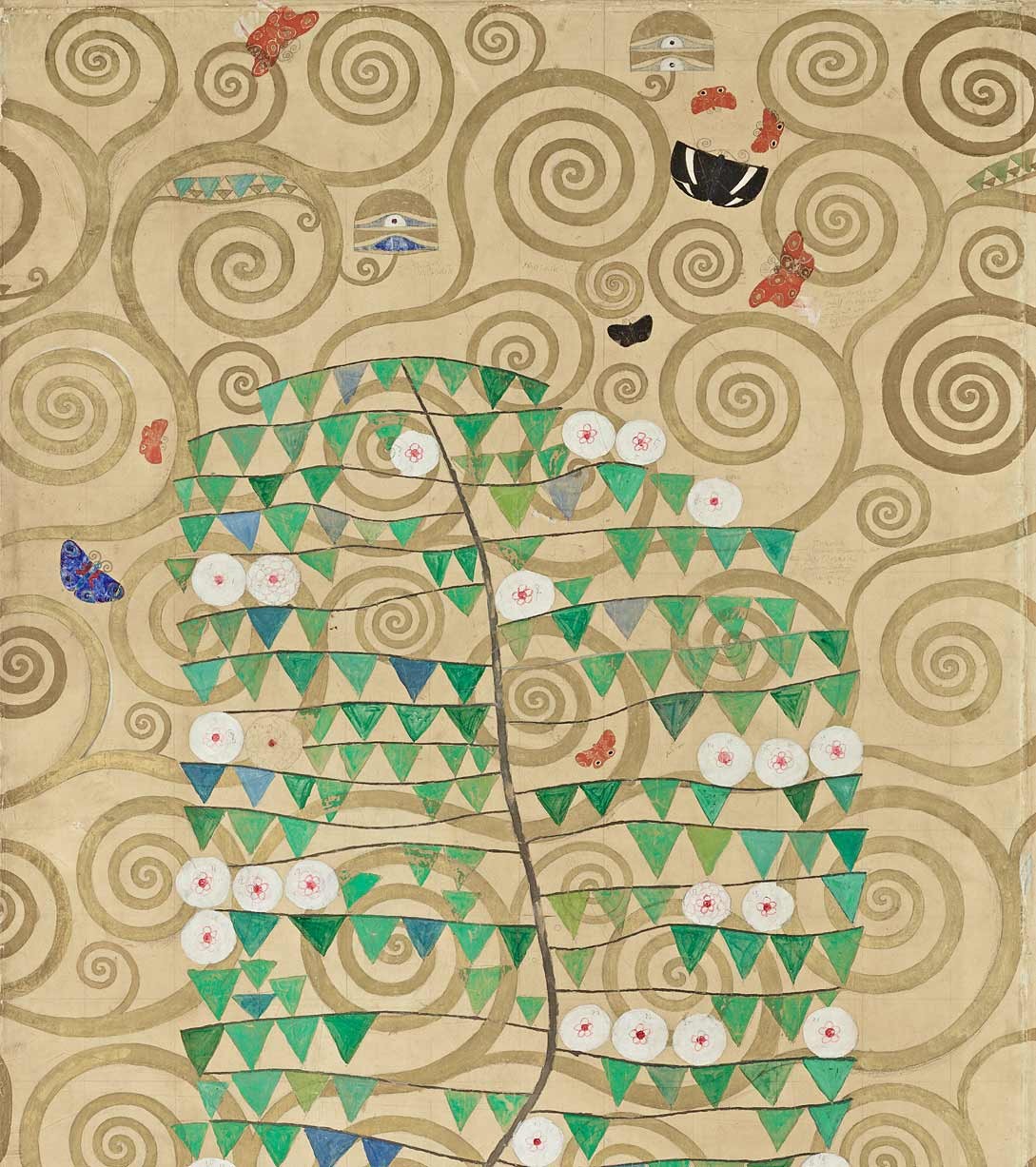

This two-year EU project is dedicated to the scholarly research and digitization of selected Art Nouveau-era objects, ultimately providing online access to the public via Europeana, a multi-media Open Access data base dedicated to the collection and publication of European cultural assets. The MAK, as one of 23 participating institutions from all over Europe, thus has been offered a unique opportunity to publicize its valuable and extensive holdings from this era—in particular works by artists from the Wiener Werkstätte and the Secession like Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, or Gustav Klimt. In the course of this project a total of 4,600 objects from the MAK’s collections, including objects presented in the current exhibitions „A Shot of Rhythm and Color“ and „Vienna 1900“, will be researched, digitized and published online until early 2014.

(Partage Plus is funded by the Commission’s ICT Policy Support Programme as part of the Competitiveness and Innovation Framework Programme)

www.partage-plus.eu

www.europeana.eu

![]()